Since 1972 and the report from Donella and Dennis Meadows, we know that there are limits to growth, that an infinite growth in a finite world is impossible. However, our societies remain obsessed by economic growth. We are trapped in a way of thinking that promotes “bigger is better” and “green growth”, with higher GDP as a solution to the problem.

High-level policies such as the European Green Deal promotes this way of thinking and do not shrink the way the EU economy is organized. The Economic growth is closely linked to increases in production, consumption, and resource use. Our current economic model affects the environment at all levels and planetary boundaries are crossed one by one.

Today, cities cover 2% of the planet’s surface. Yet they consume 75% of all materials in the economy. Many cities realize they have a big negative impact and have set ambitious goals to reduce these impacts (reduction in CO2 emissions, increase of renewable energy, reduction of waste production or energy consumption etc.)

Why is degrowth so important today?

“The other side of the story is that urban planning aims for growth, and that cities are spaces of growth. . Growth of land, growth of production, growth of inhabitants and of housing size.” (Planning degrowth, Laurens van der Wal, March 2020). Urban areas compete to attract highly skilled human capital, jobs and economic activities, to be on the list of the most attractive cities in Europe or to have the best university.

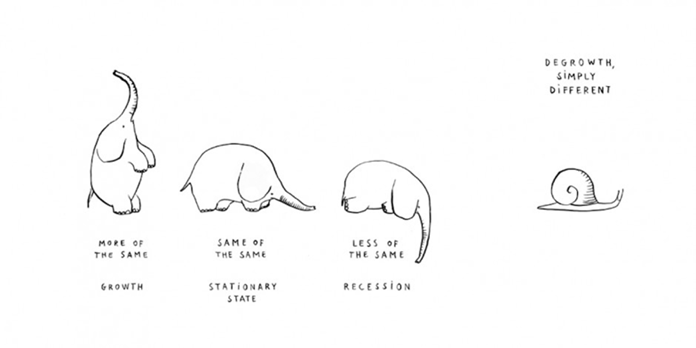

According to Tristan Riom, city, and metropolitan councilor in Nantes, “most cities don’t accept their ecological boundaries because it will mean constrain their development. It is obvious that cities need to both downscale and slow down their metabolism if they want to fit within their ecological boundaries. Attractiveness can be counterproductive and does not necessarily bring prosperity to the territory and its inhabitants.” The 2022 IPCC report and particularly chapter 5 “demand, services and social aspects of mitigation” is an ode to degrowth and sufficiency, calling for a radical reduction in demand. Degrowth is about downscaling the production and consumption, increasing human well-being and enhancing ecological conditions and equity. According to Tristan Riom, degrowth is a provoking concept “to rethink what we take for granted and rethink the role of the economy. At local level, the debate around what should grow and what should degrow must happen in all territories.”

Degrowth is about answering people’s needs to ensure that no one is left falling short on life’s essentials as defined in the Doughnut model

A degrowth urban agenda is about making cities more autonomous and moving away from a single model. Every territory should follow its own paths. It is about focusing on local needs, resources, and solidarity. Cities needs to organize local debates with citizens, business, and all stakeholders to rethink their development model within and between territories. This will enable them to collectively acknowledge their ecological boundaries, as set in the Doughnut economic model, and collectively deliberate about the type of activities that should grow or degrow.

The case of housing in a society of degrowth

A resource that is not regulated as a common good will be regulated by price. It is particularly true for housing. The financialization of the housing market and real estate speculation led to high prices unaffordable for most of the urban population. Not for profit and affordable housing should be the new norm. Taking the control of the housing market might not be easy for local authorities without the intervention of national governments. But local authorities can already acknowledge the issue and experiment new models to be replicated at a larger scale.

If you want to explore further the degrowth concept, have a look at the resources below:

- Economics for Rebels

- The stationary city (la ville stationnaire – in FR), Philippe BIHOUIX, Sophie JEANTET and Clémence DE SELVA

- How can degrowth be applied to cities

- Zagreb event

- Beyond Growth 2023 conference

This article is part of the “Decoding Sufficiency” series of articles. Subscribe to the “resource-wise and socially just local economies” hub newsletter to read future articles.