For cities to achieve their decarbonisation, they need greater staff resources

Our recommendations for cities to realise their heating planning and implement decarbonisation projects

Cities’ employees are the architects of the local energy transition. The lack of human resources is currently one of the main barriers to the decarbonisation of buildings, along with the lack of financing, technical capacity, lack of awareness, stakeholders’ engagement, and data availability.

In most of the EU Member States, local authorities are in charge of conducting master energy planning, and especially heating planning. This helps them define their needs, the availability of renewable resources and the path towards decarbonisation of their building stock with different scenarios. Based on this comprehensive and holistic plan, cities can then implement decarbonisation projects for buildings according to the needs and resources of the different neighbourhoods.

This energy planning is a long-term process. It can take 6 to 12 months to develop a heating plan, depending on the size of the city and the level of details of the plan, while the implementation of projects takes 5 to 10 years. This means that cities must employ skilled people in the long term.

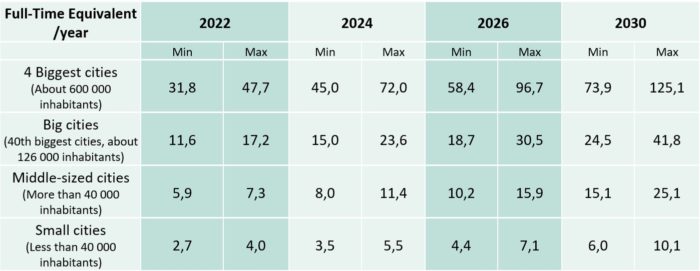

A study commissioned by the Dutch Public Administration Council in 2020 can serve as reference to quantify these needs. It intends to evaluate the implementation costs for local authorities between 2022 and 2030 as a result of the Dutch Climate Agreement voted in 2019. Indeed, the law states that in the building sector, “municipalities take the lead in a local, participative approach, to make housing emission-free, neighbourhood by neighbourhood”. The main key findings of the study are the results presented in the table below:

Data from Andersson Elffers Felix study (2020)

A city like Rotterdam for example will need, in 2022, between 31.8 and 47.7 full-time equivalents to realise the different actions identified and to more than double its staff resources by 2030. In parallel, a medium city, such as Delft, will require between 5.9 and 7.3 full-time equivalents in 2022 and triple the staff resources by 2030.

This study has evaluated different tasks that local authorities should perform at the neighbourhood and city levels. These include, among others, the design and implementation of the energy planning, communication activities, stakeholders’ engagement, monitoring, etc. The most staff-consuming tasks are also among the most important ones, namely:

- Drafting neighbourhood implementation plans

- Implementing these plans and guiding residents

- Providing municipality-wide communication (including energy one-stop-shops)

Thus, this unique study gives us an insight into the immense needs for cities. It must of course be adapted to national contexts, the cities’ strength and ambition, and the methods and tasks given to local authorities.

To cope with these staff resources requirements, cities can either directly employ staff with technical skills or delegate the work to external engineering consultants. In either case, this comes at a cost, and small and medium-sized cities often lack the financial capacity.

Cities need solutions in order to realise their heating planning and implement decarbonisation projects. We have identified five key recommendations:

- Encouraging cities to join their efforts in communities of municipalities or by establishing rural partnerships to pool financial and energy resources;

- Directly financing cities via different national or European programmes such as the LIFE European programme (find out more in our paper on how the LIFE programme can be successful in contributing to transforming the EU into the world’s first climate-neutral economy);

- Increasing their skills for them to find private and/or public funding themselves, as the EUCF project does at a European scale. Energy Cities would like to see it massively developed, but also adapted on a national or regional scale, as explained in our paper;

- Allowing local authorities to participate in the governance of the different European and national funding programmes dedicated to the regional and local levels, to express their needs and opinions on priorities;

- Fostering capacity-building, returns of experiences, peer-to-peer training, and capitalisation of existing tools. If this does not create new workforce, it can at least favour the replication of best practices, also in terms of resource efficiency. This is what Decarb City Pipes 2050 aims to do for example, drafting roadmaps towards decarbonised heating and cooling systems by 2050 for seven European cities.

These solutions can be multiple and combinable, and they might not all be put in place at the same time. But if cities are to achieve their decarbonisation, they need the human and material support to do so!